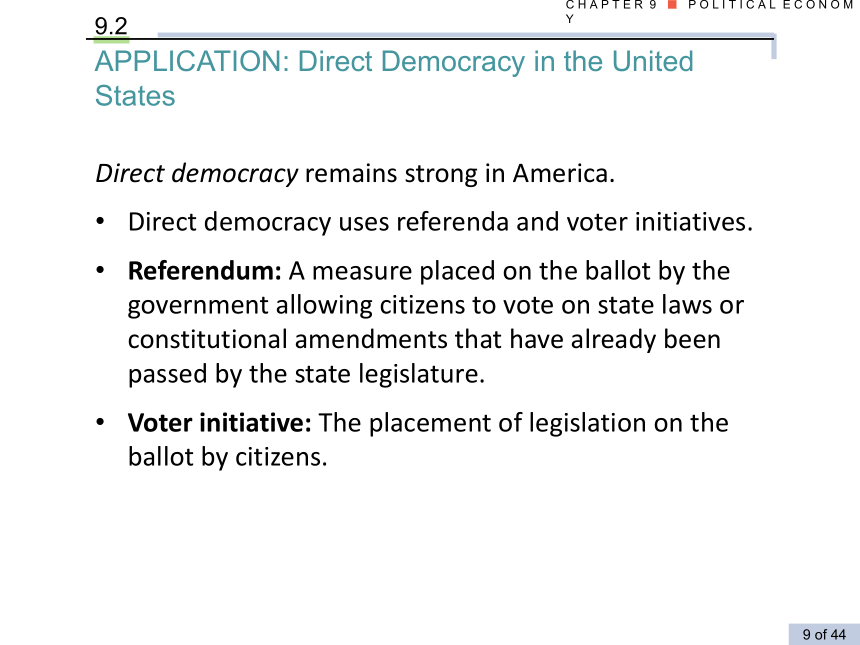

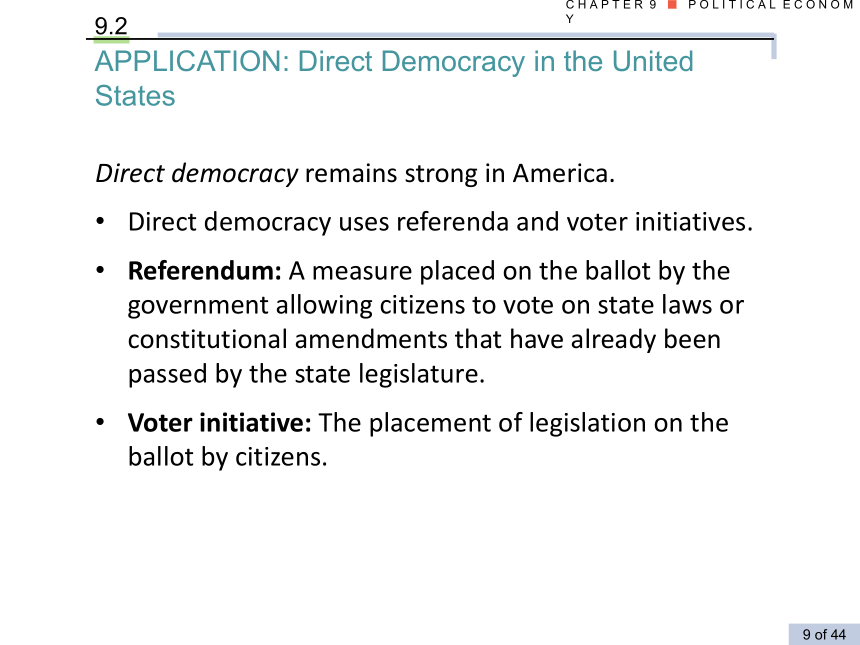

资源预览

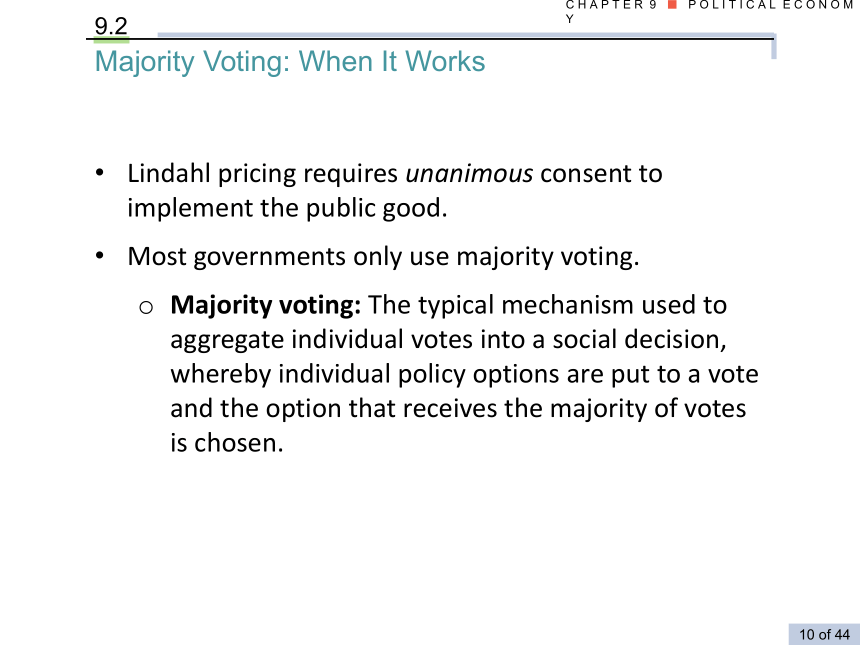

资源预览

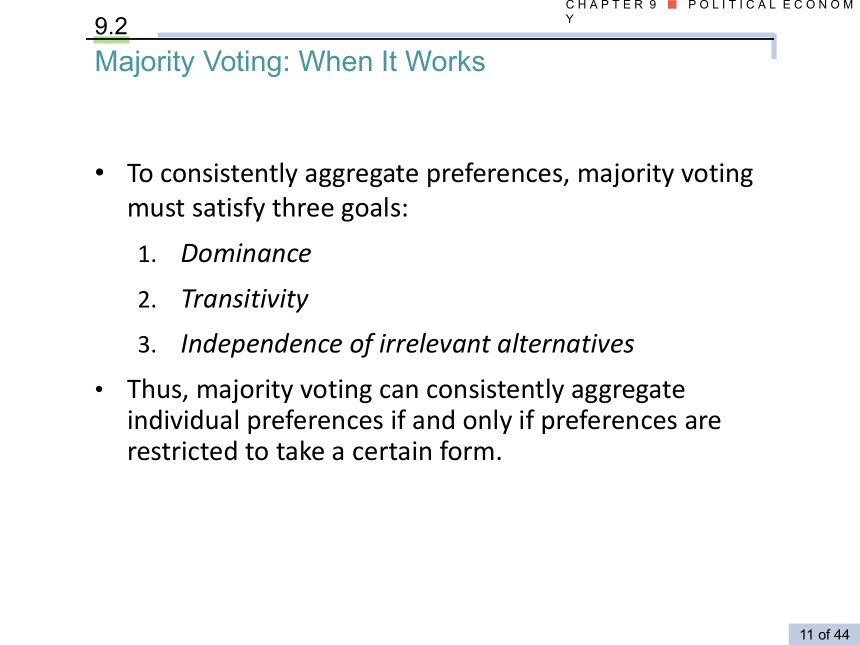

资源预览

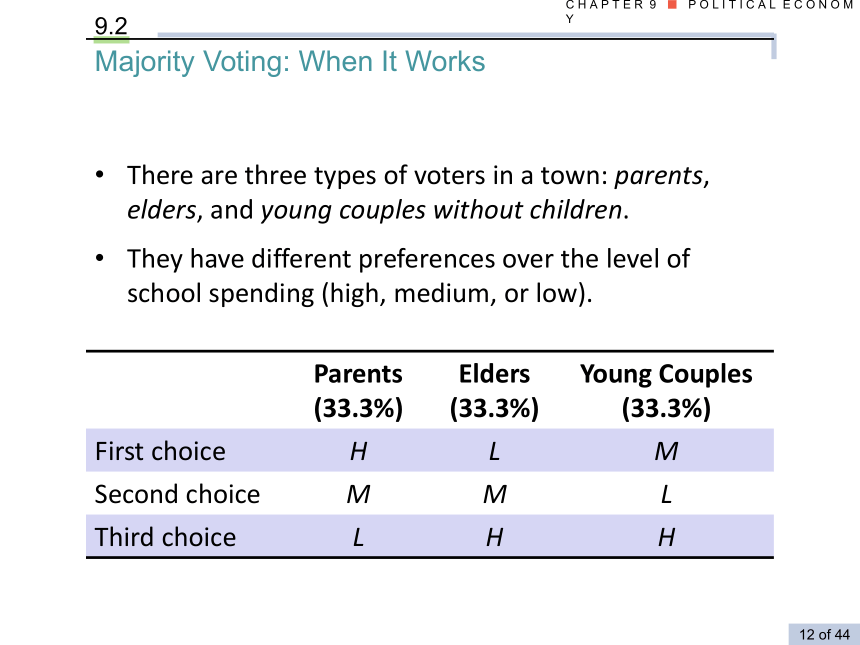

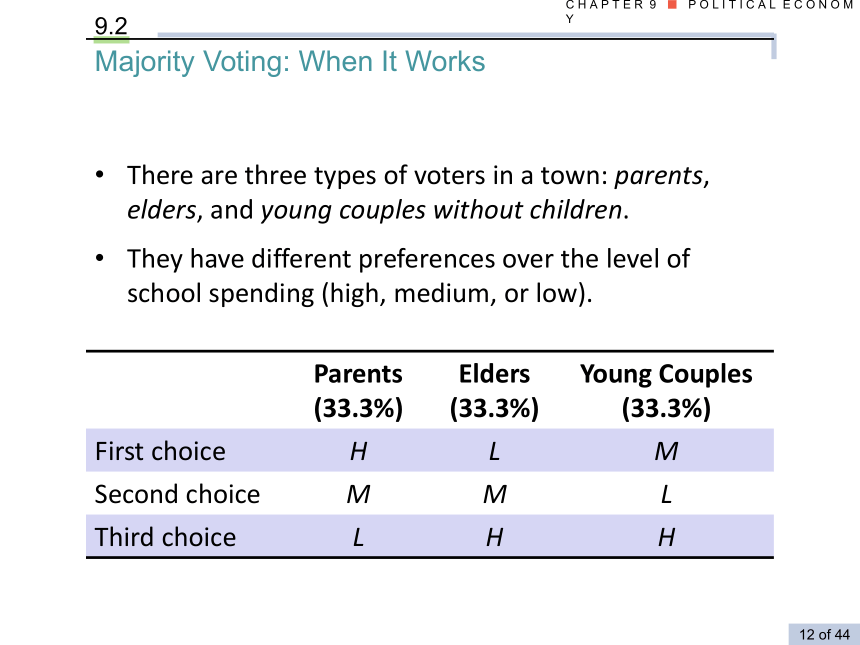

资源预览