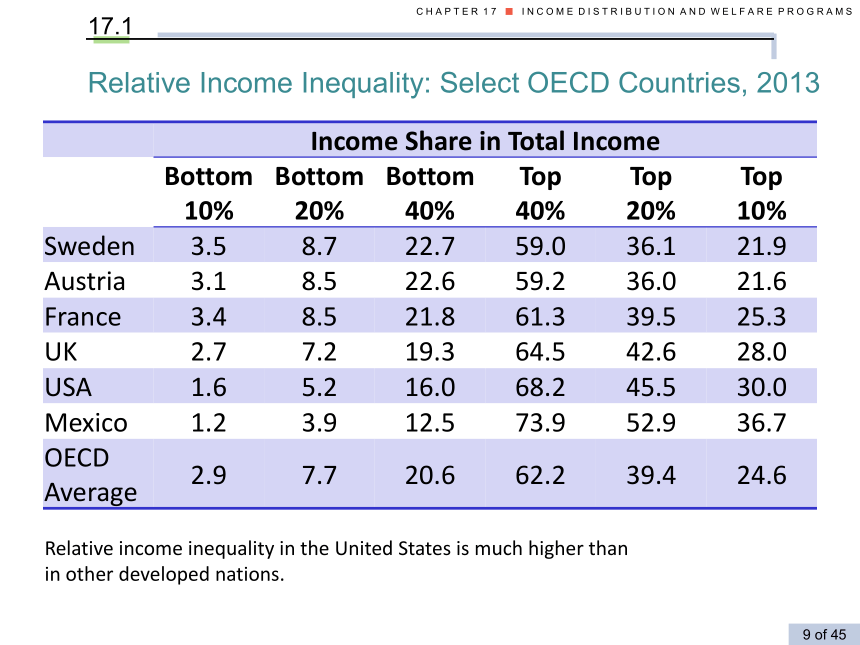

资源预览

资源预览

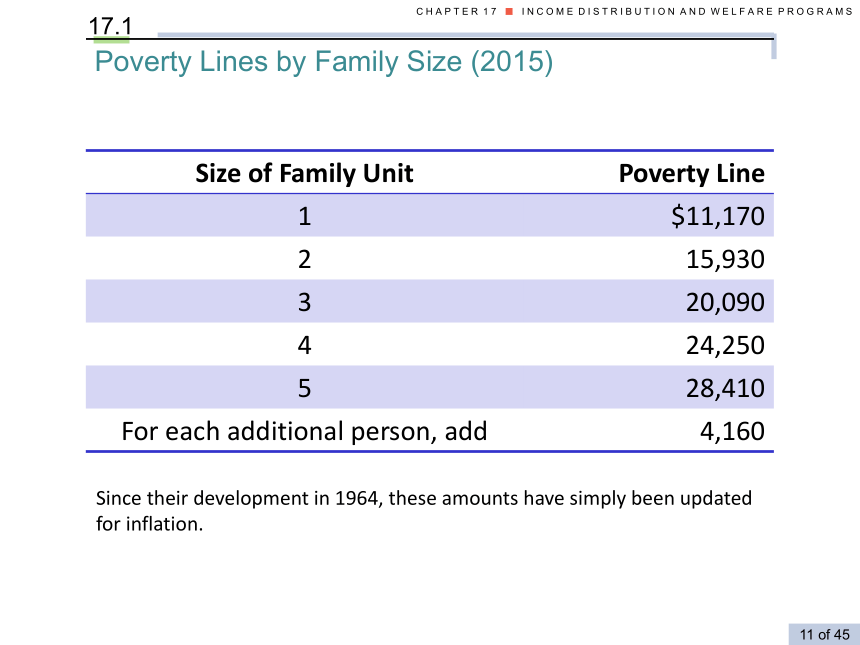

资源预览

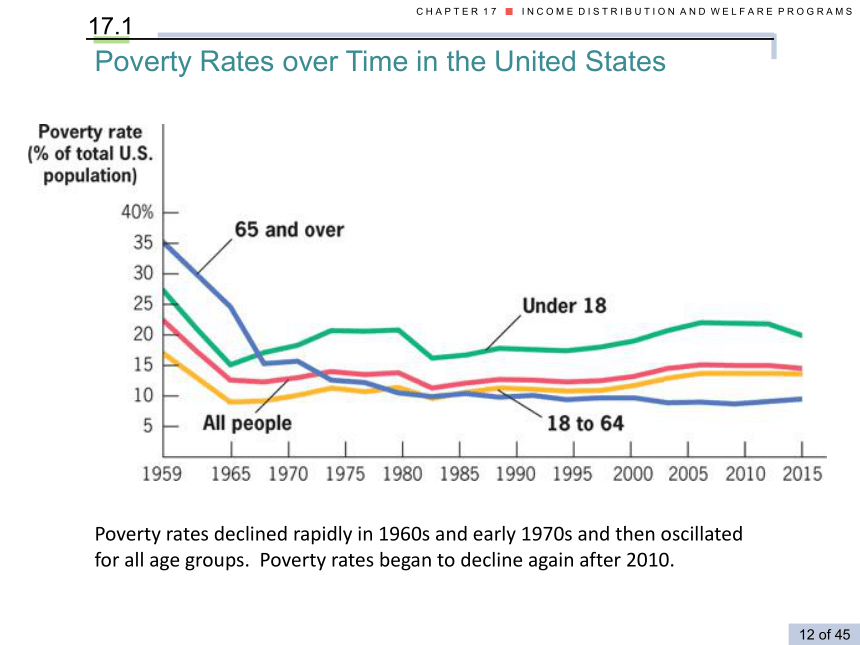

资源预览