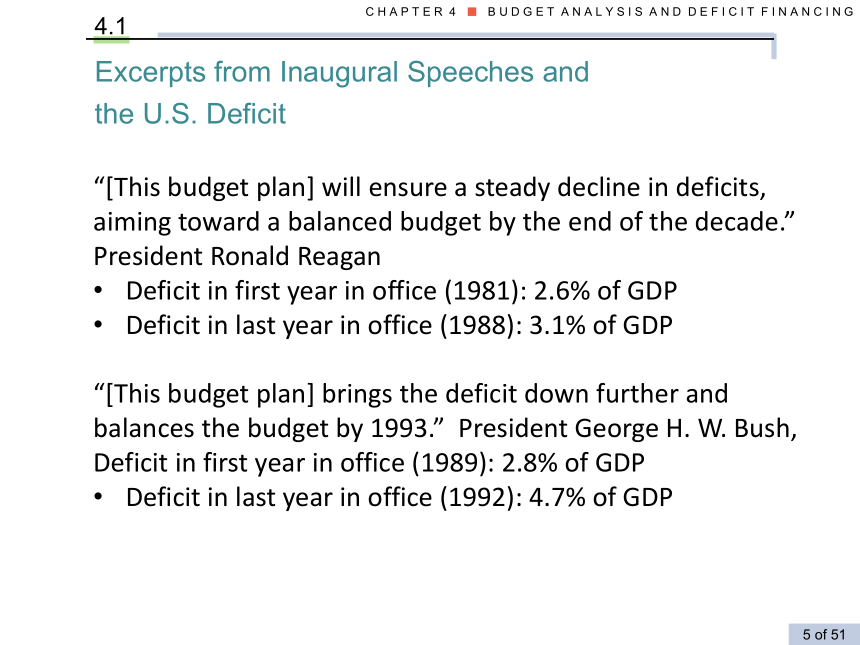

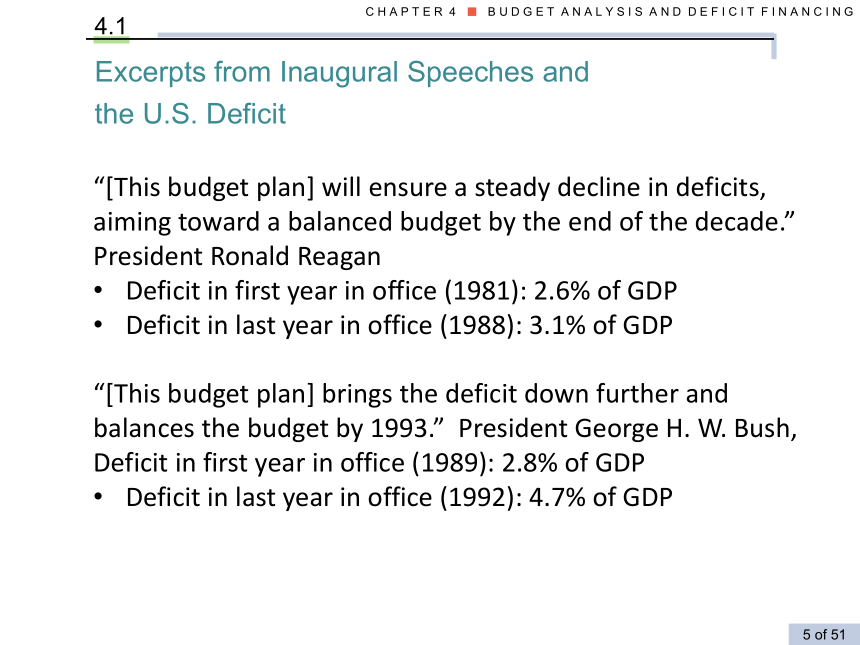

资源预览

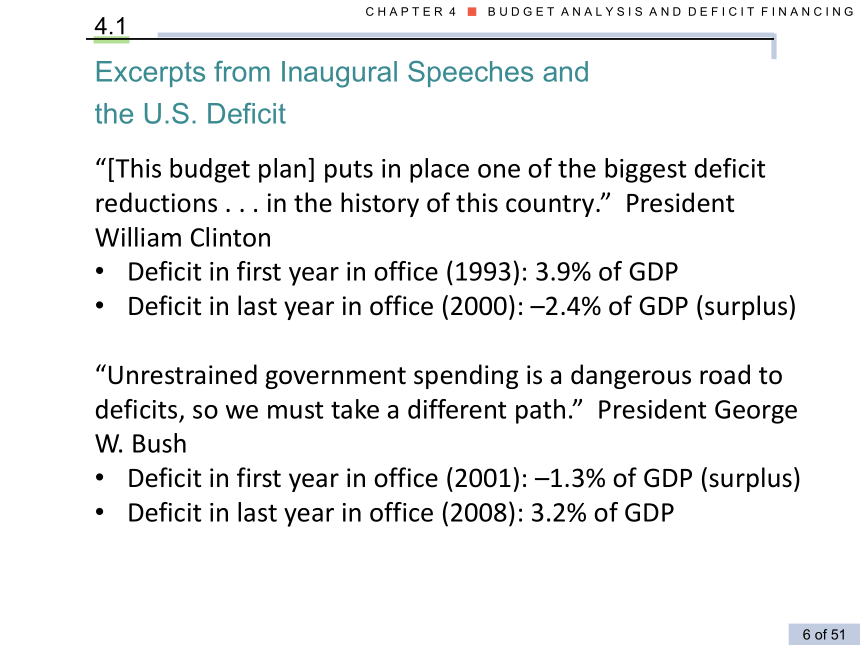

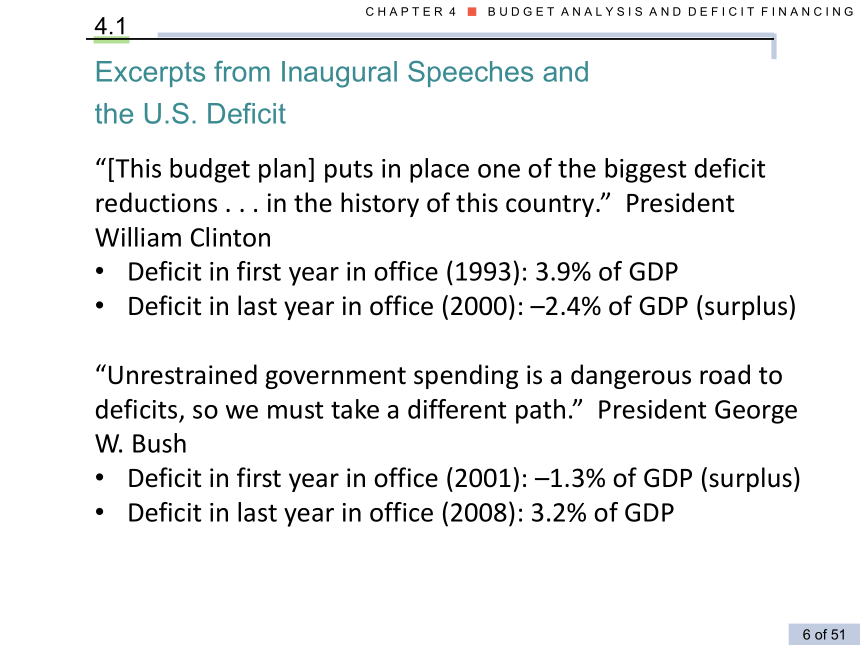

资源预览

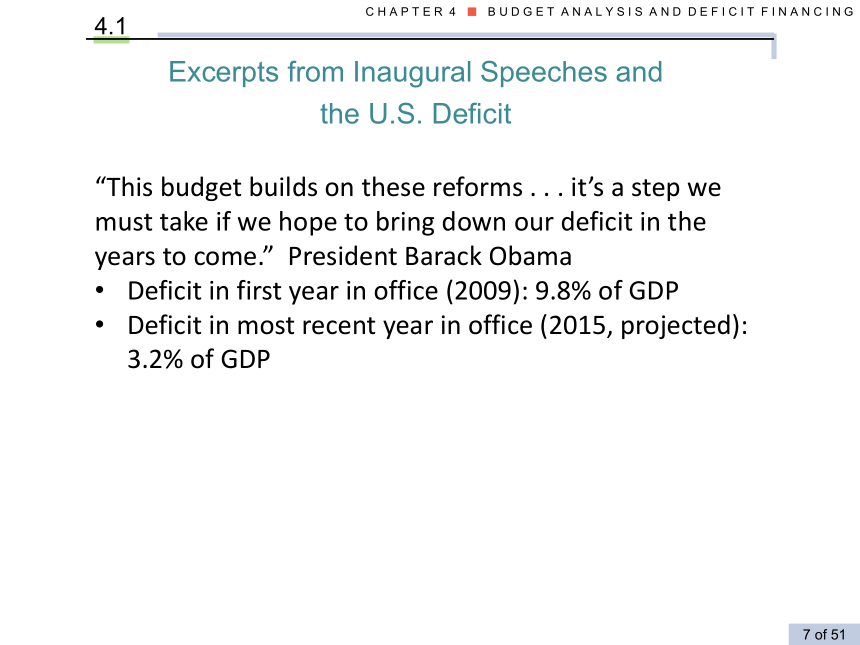

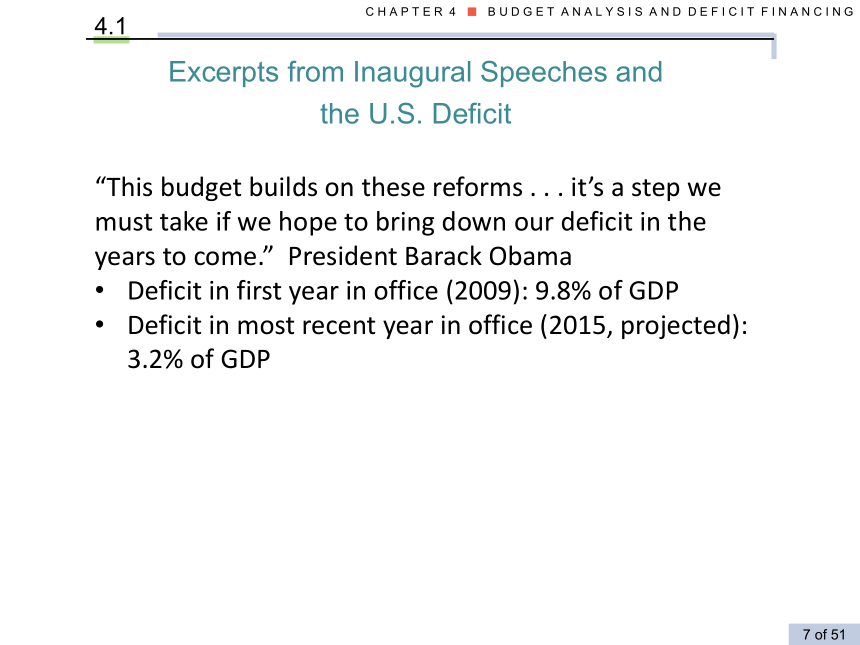

资源预览

资源预览